Case Study: Developing Structural Analysis Tooling for Experimental Aircraft

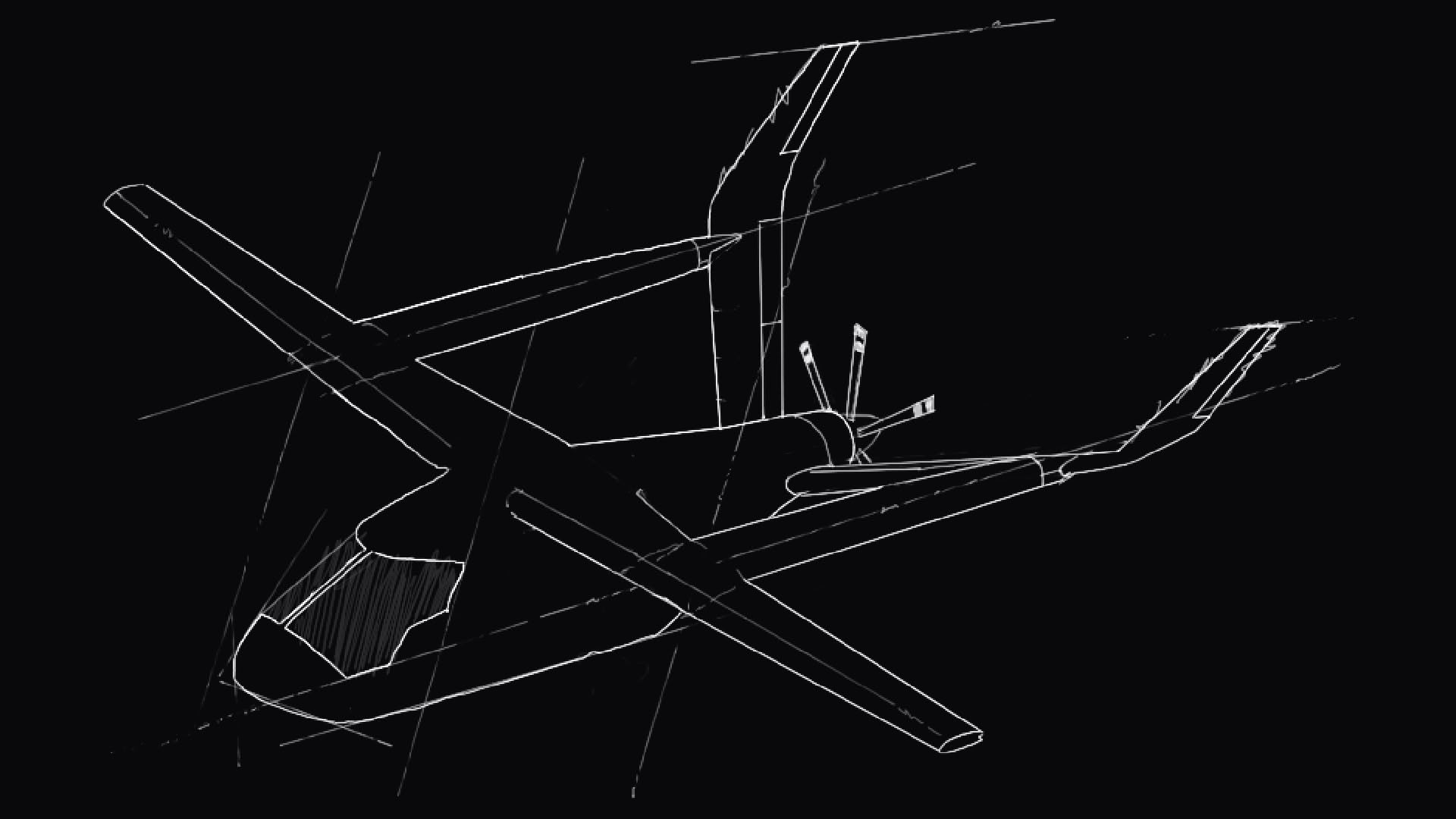

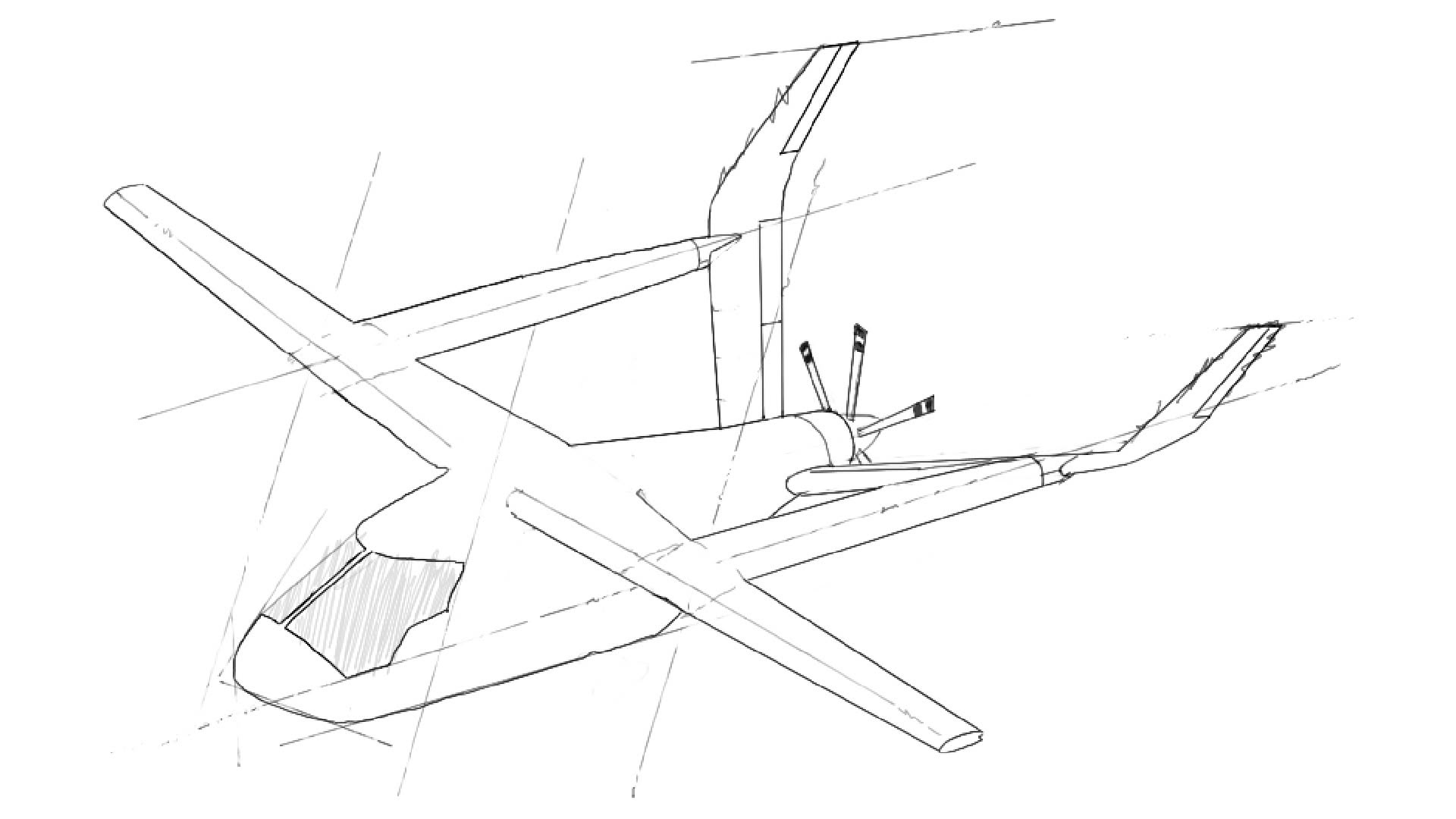

Meet the Alia CX300. She's an electric, fixed-wing, conventional take-off & landing plane, rated for 336 nautical miles at 153 knots, in under an hour of charge!

BETA Technologies, the company that I interned for this past Winter, is currently working on getting her FAA certified.

In very broad strokes, part of demonstrating the airworthiness of an experimental aircraft is showing that it can withstand a multitude of extreme loads under a variety of environmental conditions and operational scenarios.

Before designs can be built on the manufacturing floor, specific load levels first need to be met.

- A Limit Load is the maximum load expected during normal service; the plane cannot experience permanent deformation under these loads.

- An Ultimate Load is typically 1.5x the limit load. The plane's structure is allowed to permanently deform under the ultimate load, but it must be able to withstand it for at least 3 seconds without failing catastrophically.

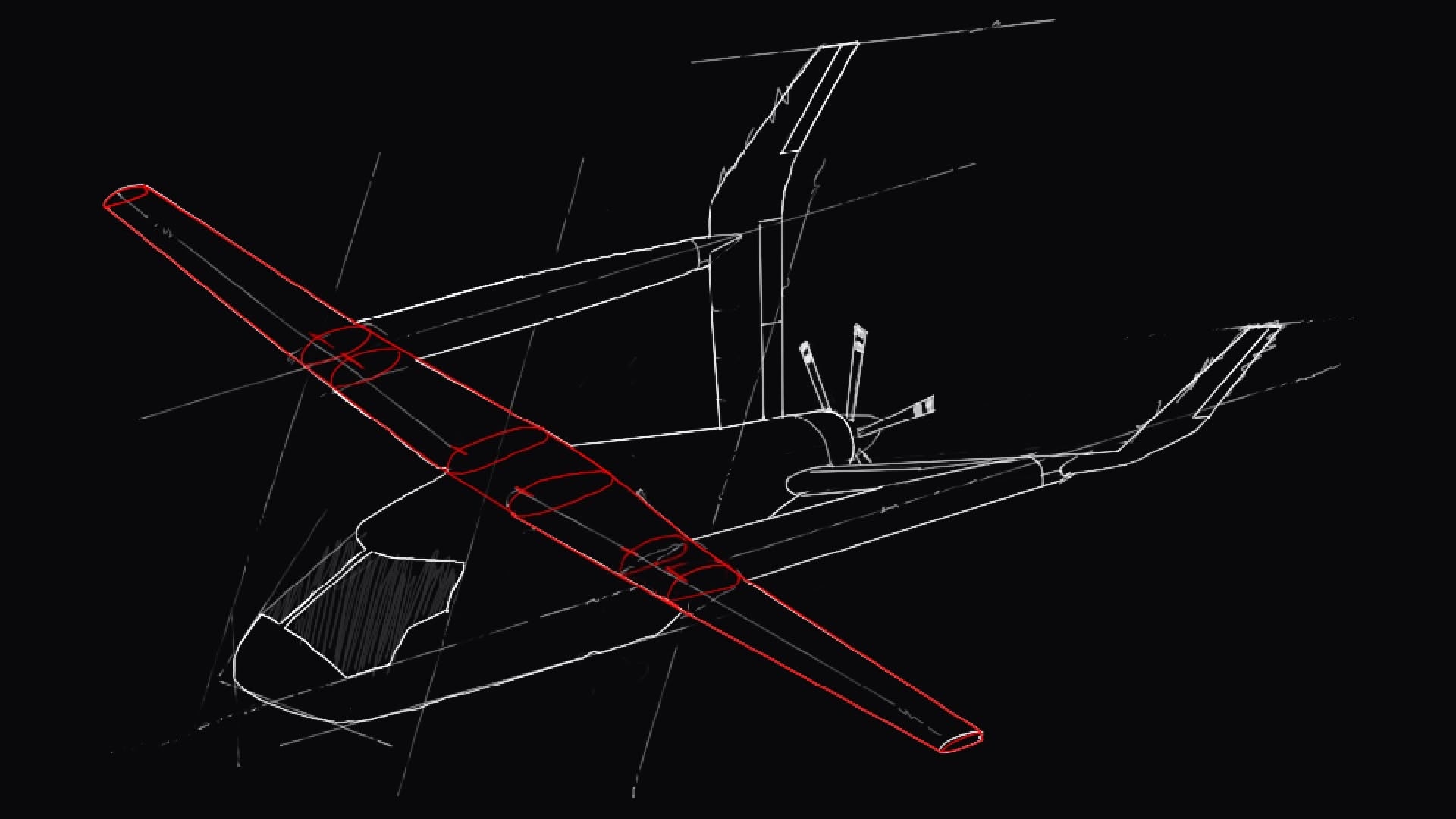

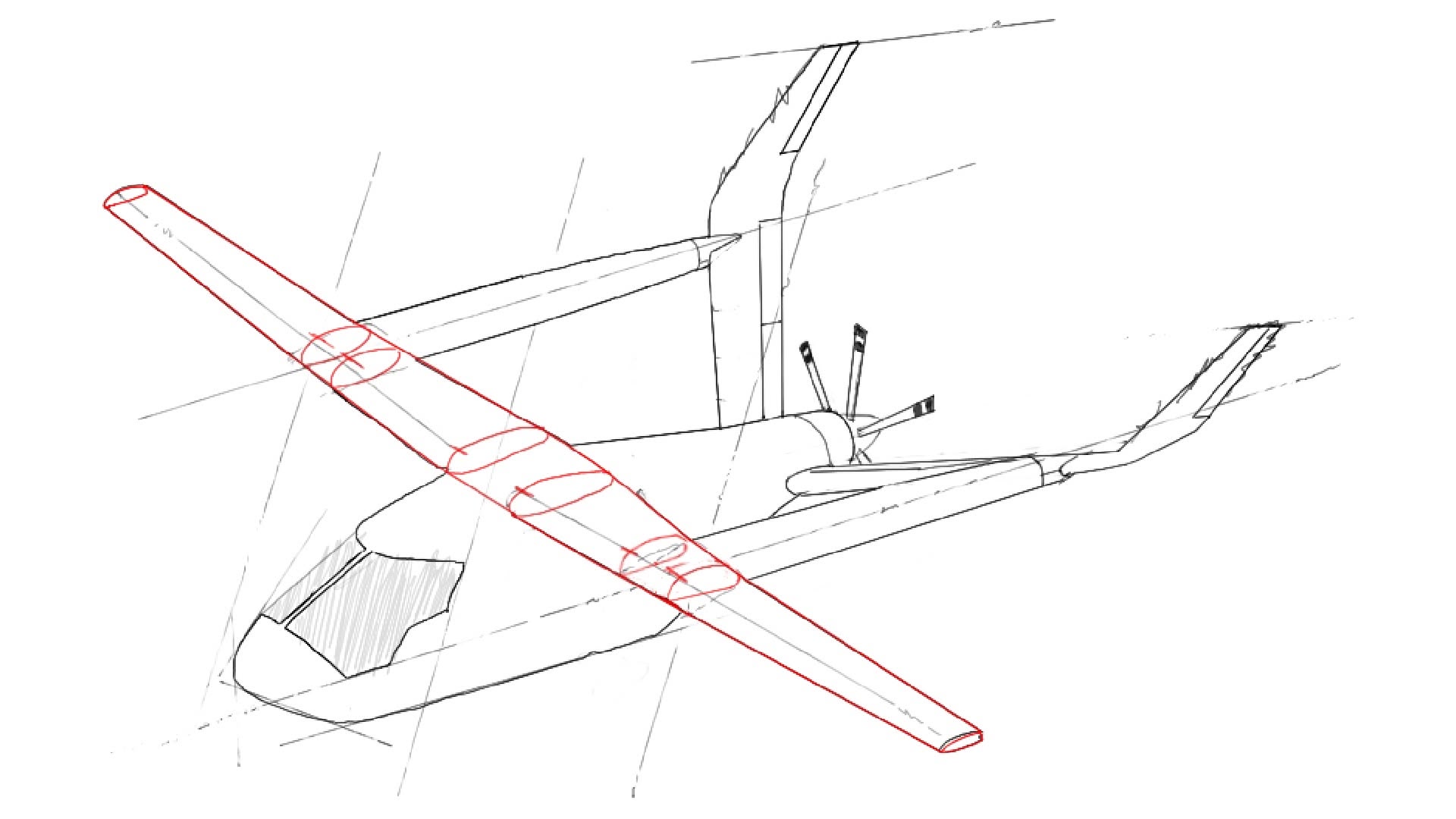

So, let's say you're tasked with analyzing the Alia's wing structure and testing it against those load thresholds. The model you are working with consists of all the elements, nodes, and materials of the entire aircraft. This is because you need to find out how the wing structure reacts under loads in conjunction with the fuselage, not just when it's floating by itself.

Running that analysis, however, can be a huge time-investment, depending on how complex the other parts of your model are. For example, if the nose is modeled as a million little finite elements, it's going to take a lot longer to get a read on your wing than plausible.

Not all hope is lost, though! By pre-calculating the stiffness matrices and load vectors at the boundary nodes where the wing meets the rest of the aircraft, you can create what's called a 'Superelement' for the fuselage. This Superelement captures all the structural behavior of the fuselage but condenses it down to just the boundary interface points, allowing you to run analyses on just the wing without worrying about the time-sink that the rest of the model would incur.

This process of separating the wing from the plane sounds straightforward in theory.

In practice, it's far more complex. NASTRAN, the industry-standard structural analysis software, represents aircraft through Finite Element Models. These models contain millions of cards, which are structured text data containing a variety of fields; used primarily to detail the elements, coordinates, materials, and constraints of the model. Most cards carry a similar base format, with fields to specify the card type, the ID number, the grid points it occupies, and the coordinate system it exists on.

Together, these cards create a run-deck representing the finite element makeup of an aircraft, and structural analysis programs like NASTRAN use it to calculate stress distributions, deformations, and failure modes.

So to separate the Alia's wing from the body, you'd need to:

- Identify all elements cards belonging to the Residual Structure (wing)

- Identify all elements cards belonging to the Reduced Structure (rest of plane)

- Find the boundary nodes—the subset of node cards that belong to both residual and reduced elements (where the wing connects to the fuselage)

- Create two separate models from the original: one with the reduced structure elements commented out (wing-only model), and another with the residual structure elements commented out (superelement model), while preserving the boundary nodes in both

You would then run the Reduced Model to find the stiffness matrices and load vectors at the boundary nodes, include those in the Residual Model, and voila! You've successfully optimized the performance of future finite element analyses on the wing.

This pre-processing phase usually takes up to three days of work, as the sheer volume of data makes it error-prone and incredibly tedious. This is exactly what I set out to automate during my internship.

This was the challenge: parsing millions of finite element model cards and modifying them while preserving their original context. Unlike typical data processing, where you might not care about the original format, or the state of its compiled form, structural engineers depend on file organization and comments for understanding complex models. Because of this, I needed to find a solution that would maintain the run-deck file structure when writing out modifications, and preserve all internal card formatting and surrounding data (headers, comments, etc.).

Due to my unfamiliarities with the NASTRAN card definitions, my first instinct was to find any existing open-source solutions and see what I could learn from them. I discovered pyNastran, a Python library designed for reading and writing NASTRAN files. It was excellent at parsing hundreds of card types and allowed me to quickly understand the intricacies of card types I needed to parse and modify.

The project seemed to be on a fast track until I hit a critical roadblock: writing changes to files. pyNastran's approach was to flatten the entire model, consolidating dozens of logically-separated files into a single, monolithic object. When it wrote the data back out, the original file structure, card syntax conventions, as well as deliberate comments and formatting were all destroyed. It had undergone a process of minification, where all 'unnecessary' elements of the model had been removed.

While it initially felt like I was back to square one, the time I spent with pyNastran ended up informing the structure of my next approach. Having seen its architecture, I now had a much clearer picture of how to design my own card classes and parsing logic.

This led to the creation of the fem-deck-tool—my custom library built specifically for parsing and modifying the Finite Element Model representations of aircraft.

Learning from my previous effort, I designed the fem-deck-tool around one guiding principle: preserve everything. It reads and understands the entire web of NASTRAN run-deck files, but it never loses track of where each card came from, what comments were next to it, or its position within a file. It creates a rich, queryable representation of the aircraft model while maintaining the original file structure and card formatting when writing out modifications.

The fem-deck-tool was developed alongside the dmig-tool—the automated substructuring process that would end up replacing the arduous preprocessing needed when optimizing for finite element analysis on just the wing.

The dmig-tool required multiple types of complex operations on the same massive dataset: removing irrelevant load cases, commenting out hundreds of thousands of cards, and adding and moving cards to the top level of the file hierarchy. Around halfway into my implementation, I realized I was doing a separate pass through the entire run-deck per each operation type. I had only been testing with smaller run-decks, but on multi-gigabyte models, I could only imagine how hilariously long that might've taken.

My solution was to design a single-pass batch processing system. First, after parsing the run-deck, I collected, organized, and verified all the requested card operations—checking for card existence, linting correct types, and separating operations into a logical order. Then, I traverse the file tree just once, applying all relevant card operations as it visits each file. I implemented logical flags that allowed the system to exit files early without needing to scan through all its lines by using a top-level dictionary to cross-reference any relevant data that might be requested by an operation in constant time.

Another issue emerged when I discovered that some cards could exist multiple times—and not within a single file, but scattered anywhere across the run-deck. For these cards, their field values are the sum of all their instances. So no complaints from NASTRAN's parser, as it's technically legal, but big complaints from me, who had only accounted for unique (card_type, card_id) combinations, which was insufficient for these cases. To solve this, I initialized a central set for each list_card that I needed to alter, during the operational phase. It would track all instances of these cards across every file. As each file was visited, it checks for any list_cards, modifies them according to the specified operation, and updates the central tracker. This process continues until all instances of all list_cards are handled, ensuring that every occurrence is processed efficiently and correctly, no matter where it appears in the run-deck.

However, the fem-deck-tool's magnum opus feature only came with the dmig-tools need to generate two different versions of the parsed model from a single shared state ( step 4 optimization ). My implementation thus far couldn't handle this because any card operation was a destructive change to the in-memory model with no history. Modify the fields of a load case and needing the original value? Whoops. Remove a card in the Reduced that the Residual needs? It's like it was never there. The only way to "go back" was to re-parse the entire run-deck, which would take too long with larger models.

But I had an idea. Remembering absolutely nothing at all from my systems design class, I decided I was going to implement an undo state. Every single card operation is recorded as a change object and appended to a stack. The undo() method then pops the last batch of changes (which can be hundreds of thousands at a time) and precisely reverses them, with logic to handle complex scenarios like prioritizing the reversal of move operations to ensure that any included files adjusted their indices as other operations that removed or added lines to a file were undone. This way I could retain access to the locations of nested files in a dictionary even after undoing large amounts of changes.

To give an idea of the scale and amount of data this method needed to handle, this is what my logs looked like after one undo.

module:228 - Undoing Changes

undo:1781 - Successfully undid 229032 comment operations

undo:1781 - Successfully undid 302 remove operations

undo:1781 - Successfully undid 49 modify operations

undo:1781 - Successfully undid 0 uncomment operations

undo:1781 - Successfully undid 2 add operations

undo:1781 - Successfully undid 129 move operationsThis allowed the DMIG tool to apply multiple sets of changes, write the files, undo() back to the checkpoint, and then apply a second set of changes, all without re-parsing or cloning the model's state. Ultimately, I had transformed a three-day tedious process into an automated workflow that completed in under 10 seconds while preserving every bit of engineering context.

What started as a deeply specific automation task evolved into building a definitive library that any future developer or structural engineer could use to interface with any finite element model. The impact was immediate outside the dmig-tool—I retrofitted a previous Numerical Buckling tool to be faster and more accurate and prototyped a Coordinate Symmetry tool for my supervisor in only 30 minutes. Without the fem-deck-tool, just implementing the parsing and modification logic for these tools would have taken days each.

In many ways, what I had built acted as a domain-specific language for altering the finite element representations of aircraft, which act as the basis of structural analysis. It allowed engineers to express and perform structural modifications easier, through interfacing with powerful and comprehensive standard library functions, and it can be used as the foundation of developement for any future structural analysis tooling that deals finite element models.