Improvisation on the Artist

My environment is unnatural, unsensual, tough and uncompromising. Within this milieu I have decided to create my art. The painting is not the conduit. I am the conduit.

As the hour ticked onward, my family grew more and more tired of me. Apart from a painting of an evil baby that my mom really seemed to enjoy, it was clear they'd had their fair share of being dragged along through the Museum of Modern Art.

So, I made promises to be hasty with my exploration of the sixth floor, where a new exhibition had recently been launched: Jack Whitten: The Messenger.

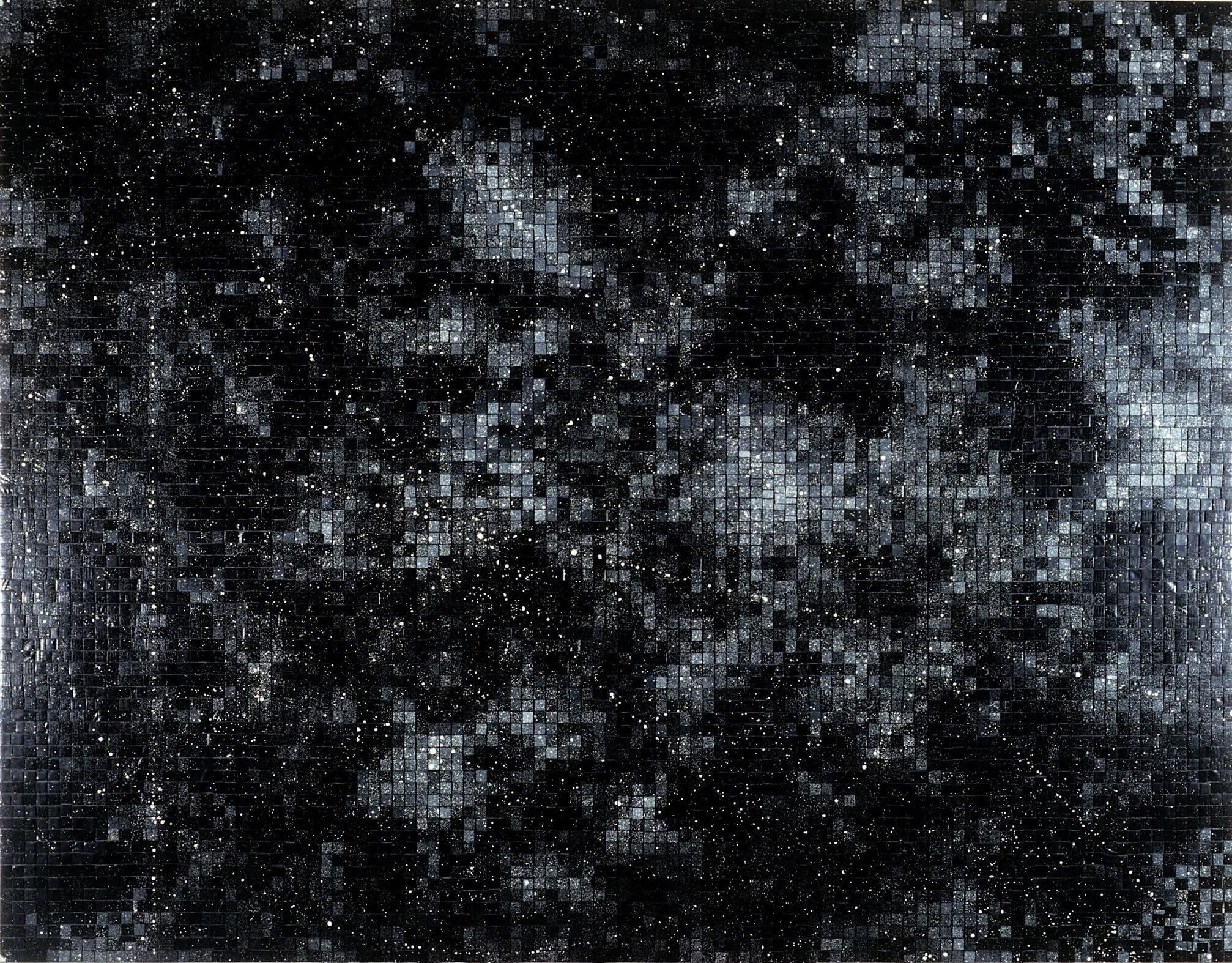

I walked up the stairs, hearing the faint whisper of So What by Miles Davis playing at the top. Reaching the landing, I became immediately drawn in by the sight of a cosmic window adorning the wall.

As my steps fell closer and closer, the painting's outer constellations began to exceed the boundaries of my vision. My burgeoning heartbeat burned up as I reached into the expanse of stars, ultimately silenced in the face of infinity portrayed behind each individual tile. Soon, the rest of me followed.

American artist Jack Whitten (1939-2018) created Homecoming: For Miles Davis in commemoration of the jazz musician, who he had been close friends with. The goal of the painting was to portray Davis's soul in accordance with how he saw it.

Whitten started by laying down sheets of acrylic and splattering individual droplets of white paint over them. After they had dried, he would carve each individual tile and rearrange them to form a "cosmic net." 1 After all was said and done, he would be left with what he called an Acrylic Tesserae, a mosaic composed of paint.

As I explored the rest of his exhibit, it became clear that Whitten had a deep connection to jazz, not just in his relationships, but in all aspects of his life and his art.

I believe that avenues exist between conceptual awe & understanding of a subject, collapsed in both directions by our experiences with it. It is up to us to color the entrances with curiosity and the ends with comprehension.

And so, I let my curiosity carry me forward.

Double Shift Originality#

For all of his life, Jack Whitten had felt a connection to jazz music.

He started as a sax player in junior high, years before he ever started painting. But after moving to New York, he knew his musicianship was not sufficient enough to participate in the experimental jazz scene.

The music was a way of me defining myself. I couldn't do it with the horn, so I figured I could deal with it in paint. 2

It became clear to me as I explored how Whitten talked about music, that he saw jazz as a conduit which bound both forms of artistry—both visual and audible. To him, his paintings were another way to create "the music," they were an abstraction on how he wanted art to define him.

Philosophy of Jazz#

To Jack Whitten, jazz represented an "expansion of freedom" 3 due to its embrace of improvisation; its spontaneous nature imposes no limits on feeling or expression.

Whitten saw improvisation as a necessary element of art. Without it, the "spirit" of art and jazz alike would, in essence, be stale and unmoving. But he also believed that spontaneity alone would not allow for art to connect with us. It needed help in the form of the "conceptual":

The acceptance of spontaneity/improvisation does not reject the value of conceptual thought. Conceptualism is a tool in the service of spontaneity/improvisation. The multidimensional sheets of sound in John Coltrane's music could not reach cognition without the conceptual. 4

Whitten parallels "conceptualism" to composition: the structural elements that underlay all forms of art and music. There would be nothing to improvise over or incite spontaneity if not for that compositional skeleton. Hence, art can not be truly felt without both elements.

Imagine, for example, what a musician might need when improvising. The forming parts of a song like the key, the time, the motifs, and the melodies serve as the structure intended for the musician to push and pull away from. Without these, the improvisation would have nothing to contradict and nothing to magnify.

Whitten wished for his own work to represent these ideas, desiring his "color to be improvisational." 5

Knowing this, it's not surprising that Whitten's philosophy on jazz can be witnessed in every aspect of his craft. His paintings were not separated from the ways in which he thought about improvisation and conceptualism. They were, if nothing else, an embodiment of those principles.

To him, he was creating jazz.

Russian Speedway#

Enter Russian Speedway, an oil painting that Whitten created in 1971.

He started by laying down the compositional foundation of the piece, pooling layer after layer of paint on top of one another. Then, using a T-Shaped tool he fashioned called the 'Developer,' he swiftly spread the topmost layer of paint in a single improvised gesture carried across the canvas.

Whitten transposed this technique onto other paintings like Chinese Sincerity (1974). The process of layering paint would always remain the same between these instances, but the moment in which it was ruptured was always executed improvisationally.

According to Whitten, it's in these moments that he has been programmed to act—to "purely conceptualize it"—like how a jazz musician can play without thinking after years of technical training. 6 It's in these moments that his paintings are made. 7

Homecoming#

I view Jack Whitten's expression of Miles Davis through the lens of how Yousuf Karsh portrayed Cellist Pablo Casals—his portrait capturing not physical likeness, but artistic essence.

The point I want to make with painting is that abstraction, as we know it, can be directed towards the specifics of subject—a person, a thing, an experience. 8

Whitten states in his studio journal that his paint is the "synthesis of concreteness plus abstraction," 9 the composition plus improvisation. If we view abstraction as the spontaneous element, we can see that Whitten directs his improvisations towards the specifics of his subjects.

In Homecoming, the subject is Miles Davis, and the specifics are the essence and soul he put into his jazz. These specifics play the same role that the key does in a musical composition.

Whitten's improvisation breaks us out of Davis's figurative key by portraying his soul through a visual medium, pushing away from and abstracting on top of its traditionally auditory nature. It is the structural element necessary for spontaneity to be achieved. But like all good jazz, there is a push and pull away from form.

Given that Davis's ability to improvise was also something so central to his style and identity as a jazz musician, he and Whitten become bound through that shared form of artistic expression. Again, we see the visual and the audible bridged together with jazz as their conduit. This expression, previously informing the contradiction of structure within Whitten's portrayal of Davis's soul, becomes the very thing that pulls it back into key.

Despite the differences in the mode and medium in which Whitten and Davis navigated jazz, I see their improvisations as the breathtaking foundation behind Homecoming.

Experimentation is the key. I believe that there are sounds we have not heard.

I believe that there are colors we have not seen. And I believe that there are feelings yet to be felt. 10

Footnotes#

-

Museum of Modern Art. Wall caption for Jack Whitten, Homecoming: For Miles Davis, 1992. ↩

-

Museum of Modern Art. "Jack Whitten Light Sheet I. 1969." ↩

-

Whitten, Jack. Notes from the Woodshed, p. 316. ↩

-

Whitten, Jack. Notes from the Woodshed, p. 411. ↩

-

Whitten, Jack. Notes from the Woodshed, p. 283. ↩

-

Sortor, Emily. "Jack Whitten's Memorial Paintings." Walker Art Center Magazine. ↩

-

Sung, Victoria. "Jack Whitten and the Philosophy of Jazz." Walker Art Center Magazine. ↩

-

Alexander Gray Associates. "Jack Whitten in Conversation.", p. 3. ↩

-

Whitten, Jack. Notes from the Woodshed, p. 367. ↩

-

Whitten, Jack. Notes from the Woodshed, p. 410. ↩